Shouhuai Xu, the Gallogly Endowed Engineering Chair in Cybersecurity and Professor in computer science, and Guenevere Chen, an associate professor in the UTSA Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, recently published a paper on USENIX Security 2023 that demonstrates a novel inaudible voice trojan attack to exploit vulnerabilities of smart device microphones and voice assistants — like Siri, Google Assistant, Alexa or Amazon’s Echo and Microsoft Cortana — and provide defense mechanisms for users.

The researchers developed Near-Ultrasound Inaudible Trojan, or NUIT (French for “nighttime”) to study how hackers exploit speakers and attack voice assistants remotely and silently through the internet.

Chen, her doctoral student Qi Xia, and Xu used NUIT to attack different types of smart devices from smart phones to smart home devices. The results of their demonstrations show that NUIT is effective in maliciously controlling the voice interfaces of popular tech products and that those tech products, despite being on the market, have vulnerabilities.

“The technically interesting thing about this project is that the defense solution is simple; however, in order to get the solution, we must discover what the attack is first,” said Xu.

The most popular approach that hackers use to access devices is social engineering, Chen explained. Attackers lure individuals to install malicious apps, visit malicious websites or listen to malicious audio.

For example, an individual’s smart device becomes vulnerable once they watch a malicious YouTube video embedded with NUIT audio or video attacks, either on a laptop or mobile device. Signals can discreetly attack the microphone on the same device or infiltrate the microphone via speakers from other devices such as laptops, vehicle audio systems, and smart home devices.

“If you play YouTube on your smart TV, that smart TV has a speaker, right? The sound of NUIT malicious commands will become inaudible, and it can attack your cell phone too and communicate with your Google Assistant or Alexa devices. It can even happen in Zooms during meetings. If someone unmutes themselves, they can embed the attack signal to hack your phone that’s placed next to your computer during the meeting,” Chen explained.

Once they have unauthorized access to a device, hackers can send inaudible action commands to reduce a device’s volume and prevent a voice assistant’s response from being heard by the user before proceeding with further attacks. The speaker must be above a certain noise level to successfully allow an attack, Chen noted, while to wage a successful attack against voice assistant devices, the length of malicious commands must be below 77 milliseconds (or 0.77 seconds).

“This is not only a software issue or malware. It’s a hardware attack that uses the internet. The vulnerability is the nonlinearity of the microphone design, which the manufacturer would need to address,” Chen said. “Out of the 17 smart devices we tested, Apple Siri devices need to steal the user’s voice while other voice assistant devices can get activated by using any voice or a robot voice.”

NUIT can silence Siri’s response to achieve an unnoticeable attack as the iPhone’s volume of the response and the volume of the media are separately controlled. With these vulnerabilities identified, Chen and team are offering potential lines of defense for consumers. Awareness is the best defense, the UTSA researcher says. Chen recommends users authenticate their voice assistants and exercise caution when they are clicking links and grant microphone permissions.

She also advises the use of earphones in lieu of speakers.

“If you don’t use the speaker to broadcast sound, you’re less likely to get attacked by NUIT. Using earphones sets a limitation where the sound from earphones is too low to transmit to the microphone. If the microphone cannot receive the inaudible malicious command, the underlying voice assistant can’t be maliciously activated by NUIT,” Chen explained.

Research toward the development of NUIT was partially funded by a grant from the Department of Energy National Nuclear Security Administration’s (NNSA) Minority Serving Institutions Partnership Program (MSIPP). The $5 million grant supports research by the Consortium On National Critical Infrastructure Security (CONCISE) and allows the creation of certification related to leveraging Artificial Intelligence (AI) and block-chain technology to enhance critical infrastructure cybersecurity posture.

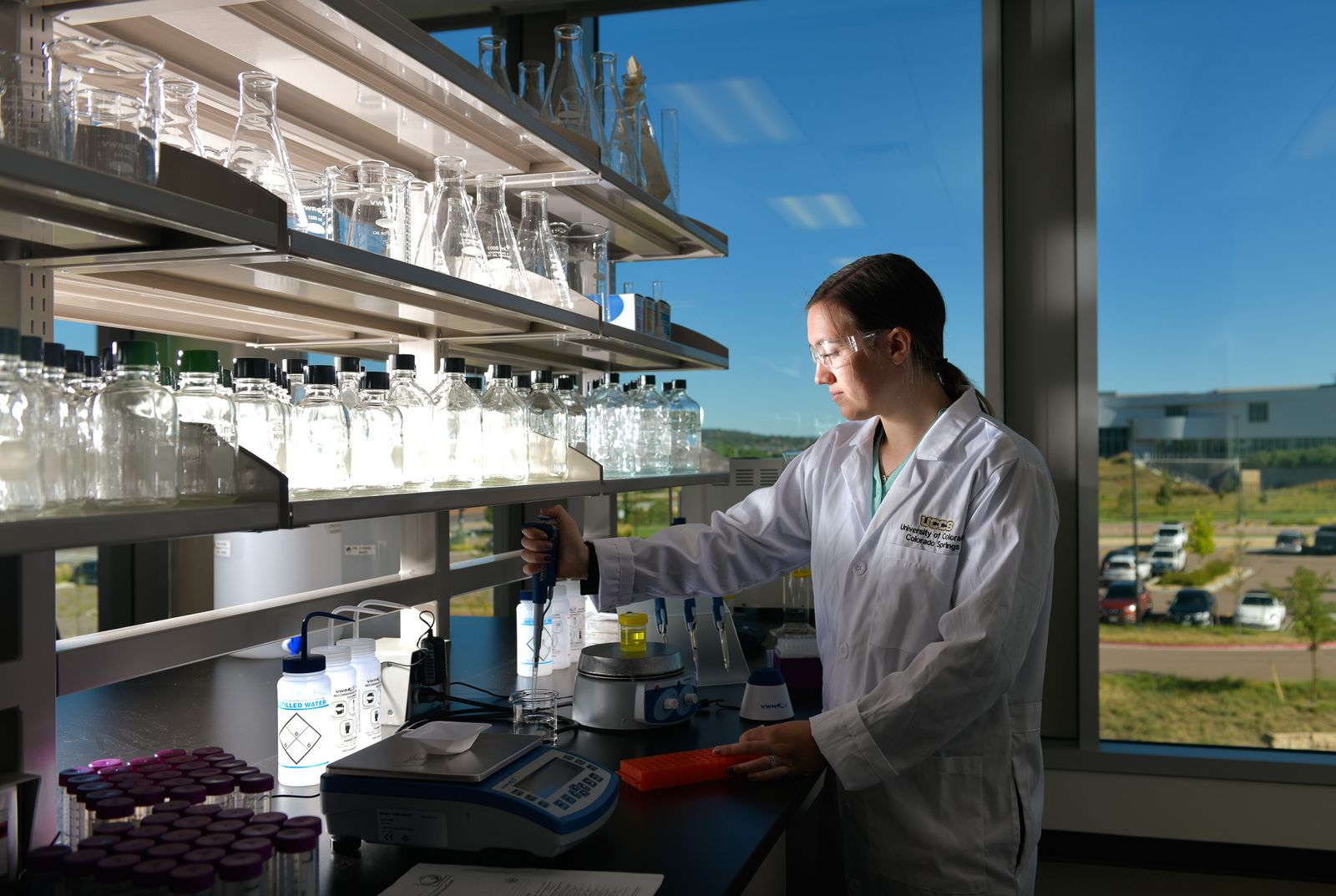

UCCS has a uniquely integrated campus cybersecurity model and is considered the center of cybersecurity education for the University of Colorado system. The university is primed to meet the cybersecurity needs of our nation, from education and research partnerships to developing the cybersecurity workforce of the future.

UTSA is a nationally recognized leader in cybersecurity. It is one of few colleges or universities in the nation – and the only Hispanic Serving Institution – to have three National Centers of Academic Excellence designations from the U.S. Department of Homeland Security and National Security Agency.